As ESG momentum continues to be driven by individuals, client demand and global events, professional portfolio managers - such as Triasima - have had to adapt by raising their knowledge level, evolve their investment strategies or work in tandem with their clients to guide them through the broad issues of ESG and sustainable investing.

Investors such as ourselves are refining their strategies with one essential goal: selecting on behalf of their clients companies with superior or increasing sustainability efforts, with the ultimate objective of building a sustainable society. This is not without its difficulties. With an increased sophistication and involvement in ESG, investors are also becoming more aware of the challenges caused by the complexity and scarcity of ESG data; concern over greenwashing; and the interconnectivity of environmental, social and economic factors.

Each year, 10 million hectares of forests are cut down, 190 million tonnes of chemical fertilizers are added to our soil[1], and 42 billion tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalents (GtCO2e) are emitted. In 2021, atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) reached 415 parts per million (ppm) and the years 2015 to 2022 were the eight warmest years on record. The global mean temperature is now 1.15°C above the pre-industrial average: to keep the global temperature increase below the Paris Agreement recommendation of 1.5°C, future cumulative GHG emissions will need to be below 380 GtCO2e.

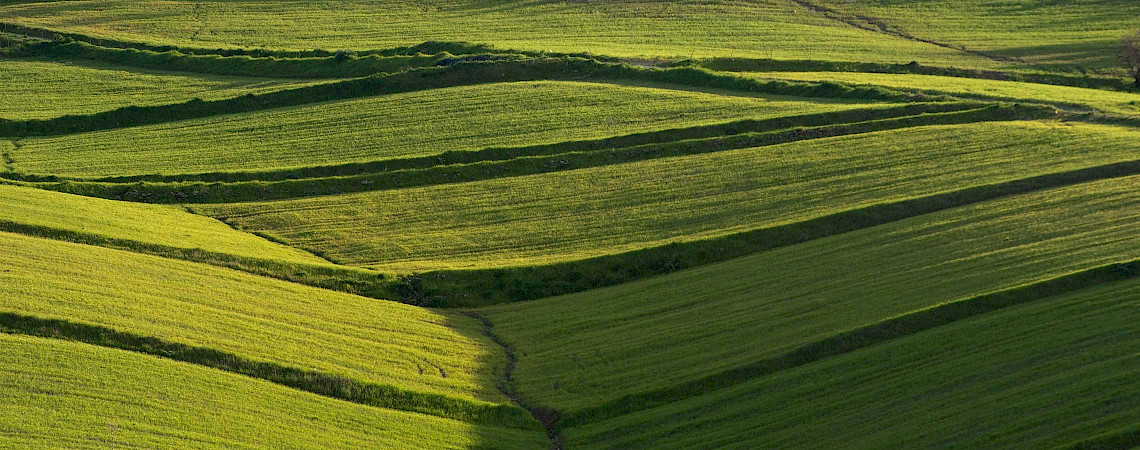

These indicators clearly show that climate change exists. To stay within safe planetary boundaries and avoid the worst effects of climate change, we need to reduce GHG concentrations to 350 ppm, add no more than 68 million tonnes of chemical fertilizers per year, and keep 75% of once forested lands forested[2]. There are, of course, other planetary boundaries and global limits to respect if we are to live in a healthy, nutrient-rich, and stable climate.

First, forests are essential to the production of biomass which is a source of food for many different species. As a result, they are home to 80% of terrestrial biodiversity including animals, plants and even bacteria and fungi. The belowground biodiversity affects nutrient cycling and carbon storage which in turn influences soil health, plant growth, water filtration, soil erosion, and carbon sequestration. So, disturbance of a forest’s biodiversity – by drivers that include commercial logging, monoculture agriculture and fires – substantially influences its ability to act as a carbon sink and its capacity to limit climate change by offsetting emissions.

Climate change also alters biodiversity by changing climatic conditions such as hot temperatures, ocean acidity, forest and grassland fire intensity and frequency, and the concentration of GHGs. This leads to a loss of habitats, a weakened freshwater cycle, soil degradation, and other cascading effects on the ecosystem and local communities.

Droughts, soil erosion and hot temperatures caused by anthropogenic climate change impact people unequally. For instance, they are very likely to affect women – who are often employed as agricultural workers in low-income countries – making it harder for them to have a secure income and provide food for their families. When people are displaced and conflicts occur due to climate change, women are also more likely to severely suffer because of a disparity in access to information, mobility, relief, and assistance relative to men[3].

Furthermore, the loss of wildlife, wild plants, and clean water due to shifts in rainwater and weather patterns disproportionally affects indigenous people, leaving them vulnerable to lower food production. This reduces their ability to provide for themselves and make them more dependent on processed food resulting in obesity and health problems.

In essence, the failure to address climate change and biodiversity challenges compromise people’s quality of life and exacerbates economic, social, and even gender inequalities, especially in fragile societies.

To address such a complex issue of climate change and biodiversity degradation, the path forward requires conviction, education, and real engagement to make a transformative change. Governments, businesses and communities need to develop their own strategies to benefit both climate and biodiversity, possibly by incorporating the following themes[4].

Protecting forests has many significant benefits, that extend beyond reducing carbon emissions. With 30% of Earth’s forests still intact and 40% of this area containing “old growth” vegetation that is more than 140 years old, reducing deforestation can contribute to reducing CO2e emissions by 1 to 2.2 gigatons per year and lower projected species extinction by 84% to 93%. Natural forest regeneration creates a complex mixture of species that is estimated to be more than 40 times more effective in storing carbon than monoculture plantations. Sustainably managed forests also provide a range of biodiversity benefits and co-benefits to local communities, such as regulating the freshwater cycle, reducing soil degradation and reducing the risk of erosion and floods.

Agriculture and changes in land use are responsible for 71% of the carbon footprint of global food production, which causes one third of total GHG emissions[5]. Both biodiversity-based solutions and technological solutions could help to reduce the carbon footprint of agricultural production and enhance its ability to adapt to climate change. Biodiversity based solutions includes agroecological strategies such as reducing tillage, using crop mixes, crop rotation, integrated farming[6], managing grazing[7], using organic fertilizers, and reducing chemical pesticides. Technological solutions include the use of climate-smart technologies such as precision irrigation to use water more efficiently. The use of these agroecological solutions reduce methane emissions from enteric fermentation and livestock manure, reduce nitrous oxide from the production of chemical fertilizers, and create soil carbon sinks by enhancing soil biodiversity.

In parallel to changes in production methods that have climate and biodiversity co-benefits, recent trends in our society have encouraged the consumption of products that are plant-based, sustainably farmed, sustainably harvested from forests, water-wise and ecologically friendly. For example, companies may promote the use of sustainable alternatives to plastic packaging to reduce waste and enhance circular economy; or may encourage the use of responsibly sourced products, with verification and certification from third parties, to combat deforestation. These strategies have been matched by a consumer desire to have more environmentally friendly products, often encouraged by incentives by various levels of governments to support innovative sustainable solutions with a positive environmental, social and economic impact.

In our investment portfolios, we favor companies that innovate by offering eco-friendly products and practices. Our collective responsibility as consumers, governments, and active investors to support innovative and sustainable business practices is essential if we are to live in a green, resilient, and healthy society.

[2] Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist - Kate Raworth - Google Books.

[3] Explainer: How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected | UN Women – Headquarters

[4] See Biodiversity and Climate Change Scientific Outcome report IPBES-IPCC Co-Sponsored Workshop on Biodiversity and Climate Change | IPBES secretariat

[6] Integrated farming is a method that mixes crop production and livestock raising.

[7] Managing grazing is managing where and for how long animals forage, and relying on their manure to build soil health and sequester carbon dioxide.